Week 1 – The Journey Starts

Stepping outside your comfort zone sometimes feels scary. It is like not knowing where the road of your journey will end, however, you know you will learn new things on the way. I connect this feeling to understanding the complicated puzzles surrounding sustainability; it pushes you outside your comfort zone, outside your own discipline and tries to understand together. The beauty of finding creative solutions for the puzzles ahead can be found in a transdisciplinary approach.

A transdisciplinary approach provides us with a new horizon of views and connects to the essence of curiosity, creativity and, above all, collaborations to connect different disciplines and create long-term solutions (Philipp & Schmohl, 2023). This approach helps us to understand the wickedness of sustainability, as currently, the environment is adapting to the demanded change we lay upon her; we ask her to change to adapt to us while we still demand the original necessities she provides, isn’t that wicked in it itself?

Embarking on the journey of learning transdisciplinary skills and sitting in class, I contemplate the complexity of how to approach wicked problems. Waddock (2013) asserts that solutions for such problems are never fully holistic, as each path towards a solution reveals new elements of the problem. I hope that I will understand this complexity more during the upcoming weeks and steer myself in the right transdisciplinary direction.

Next week will cover which stakeholders will be part of this journey, how this problem has roots, a trunk and branches, and how they all interconnect.

Week 2 – A Guidance Towards the Same Path

Picture: Akilee. (2017, November 25). What Trees Feel, How They Communicate.

Trees is a forest all rely upon, connect and communicate with each other. Walking through the forest, I’m fascinated by tree connections and pondering how humans can learn from them. In class, I explored tools like stakeholder and problem-tree analysis, and the thought of the importance of framing stuck in my mind. As highlighted in class and by Klenk and Meehan (2017) framing plays a crucial role in the problem-solving process and involving stakeholders, influencing how they represent themselves and their willingness to cooperate.

In a recent conversation with the CEO of Participatie Keuken (Ben) for a school assignment, concerns about food waste and sustainability were discussed. Ben highlights the challenge of assigning blame for food waste—whether it’s consumers, producers, or the need for more regulations. By framing the issue as a collective problem without blame, Ben emphasised the potential for fostering stakeholder cooperation.

As I reflect on this thought, I believe importance should be found in not pointing fingers towards each other on who should take responsibility but in producing mutual interest, connecting all beneficial solutions and sharing responsibility. As Hörisch, Freeman and Schaltegger (2014) state in their paper, importance is found in connecting by generating mutual interest rather than focusing on trade-offs, thereby creating value for all stakeholders involved.

Next week, I will continue my journey and come across changing landscapes, showing me that multiple roads lead to Rome.

Week 3 – The Changing Landscapes Towards my Final Destination

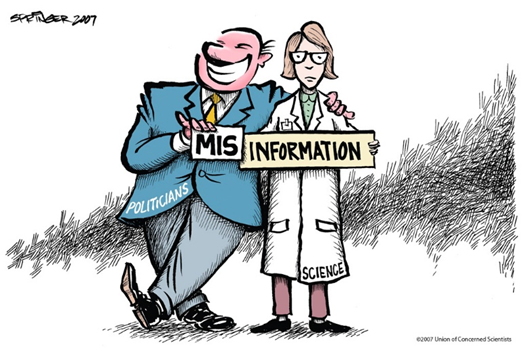

Picture: van Damme, C. (2016, October 10). Science, uncertainty and politics: An eternal struggle?

Standing at the crossroads of my journey, I wonder which path leads to my desired destination. Is it a singular yellow brick road like Dorothy’s and Toto in Oz, or are there countless choices? Will the journey transform me, and who will I encounter? In my transdisciplinary skills course, I’ve learned that the path may not be straightforward, and my decision on which path to choose is influenced and not just by me.

This dynamic relationship between both can involve science informing policy, shaping research priorities, or collaborative co-creation. Esther Turnhout (2018) underscores the interdependence of environmental science and policy, stressing their mutual value. This highlights the crucial need for co-creation, where scientists and policymakers collaborate for effective solutions, acknowledging the interconnectedness of these domains.

Co-creation is an important tool that can lead to significant and long-term change. This co-creation thought also comes into play in the design thinking process. This process includes 5-steps to creating innovative and meaningful solutions for problems regarding a specific group (Buhl et al., 2019; Sprouts, 2017). These steps are the five different landscapes I will cross during my journey; empathise, define the problem, ideate, prototype and test (Sprouts, 2017).

Reflecting on transdisciplinary, co-creation, and the different landscapes during my journey, the concept of power emerges. Questions arise about who decides which problem to solve, who participates in co-creation, and who holds the power in steering these steps. The control of power shapes our paths, just like Dorothy’s intentional journey on the yellow brick road to the mighty Wizard of Oz, yet was that the right path?

Week 4 – Did I Reach my Final Destination?

The last crossroad I stumble upon is the interface between science and art. Looking back, I remind myself of my favourite museum of all time, NEMO in Amsterdam. This museum is a perfect example of the interface between science and art; it presents science in such a way as to make it more attractive for children to get involved via the use of fun technologies and art. This collaboration explores new benefits I was unaware of, as Berry-Frith (2023) explains, it fosters creative thinking, enhances understanding, and broadens access to science, ultimately improving public appreciation for scientific concepts.

With art, there are artists. Ede (2002) explains her theory about why artists would like to participate in the science process and visualisation. The most interesting thing I found is her belief that science and art are a quest for freedom; both elements share the need to be truthful and try to present a real version of reality.

Being on a quest for freedom and understanding myself during my journey, I have crossed different landscapes, and finally, I stumbled upon a beautiful oasis of colours, a piece of art in itself. As I look closer I can see what I was looking for this whole journey, my final destination: another person. The most important lesson I learned over the last couple of weeks is that solving wicked problems is a lost cause while doing it alone, strength is found in finding solutions together as an interconnected forest.

Reference list:

Akilee. (2017, November 25). What Trees Feel, How They Communicate… http://www.ecosophical.org/2017/09/what-trees-feel-how-they-communicate.html

Berry-Frith, J. (2023, September 29). Every science lab should have an artist on the team – here’s why. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/every-science-lab-should-have-an-artist-on-the-team-heres-why-211636

Buhl, A., Schmidt-Keilich, M., Muster, V., Blazejewski, S., Schrader, U., Harrach, C., Schäfer, M., & Süßbauer, E. (2019). Design thinking for sustainability: Why and how design thinking can foster sustainability-oriented innovation development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 231, 1248–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.259

Ede, S. (2002). Science and the contemporary visual arts. Public Understanding of Science, 11(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/11/1/304

Hörisch, J., Freeman, R. E., & Schaltegger, S. (2014). Applying Stakeholder Theory in Sustainability Management: Links, Similarities, Dissimilarities, and a Conceptual Framework. Organization & Environment, 27(4), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026614535786

Klenk, N. L., & Meehan, K. (2017). Transdisciplinary sustainability research beyond engagement models: Toward adventures in relevance. Environmental Science & Policy, 78, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.09.006

Philipp, T., & Schmohl, T. (2023). Handbook Transdisciplinary Learning. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839463475

Sprouts (Director). (2017, October 23). The Design Thinking Process. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_r0VX-aU_T8

Turnhout, E. (2018). The Politics of Environmental Knowledge. Conservation and Society, 16(3), 363–371. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26500647

van Damme, C. (2016, October 10). Science, uncertainty and politics: An eternal struggle? https://crastina.se/science-uncertainty-and-politics-an-eternal-struggle/

Waddock, S. (2013). The Wicked Problems of Global Sustainability Need Wicked (Good) Leaders and Wicked (Good) Collaborative Solutions. Journal of Management for Global Sustainability, 1(1), 91–111. https://doi.org/10.13185/JM2013.01106

Plaats een reactie